The pristine state of Uttarakhand located in Northern India is one of the few states in the country that lies on the Indian Himalayan belt. It is nestled in the foothills of the Himalayan range and is known best for the density of natural resources that the state is gifted with. Rivers, glaciers, forests and peaks can all be found in the state of Uttarakhand. The diverse topography, cool climate and abundant water sources have made the state rich in biodiversity with a wealth of floral and faunal species that are unique to the Indian Himalayan ecosystem. The presence of these species has also given rise to a robust system of traditional forest knowledge management practices that have been passed down from generation to generation.

A hybrid system of community management and technical advisory from the Revenue Department and Forest Department have institutionalised in the Van Panchayat, which roughly translates to Forest Council, is a participatory approach to protecting forested land and wildlife on a micro-level and safeguarding the rights of small villages that depend on forest-based industry for their livelihoods and day to day sustenance.

via Pixabay

History

Van Panchayats were constituted as a reaction to state-imposed forest regulations back in 1931 when India was still under British rule. Since 1865, the British-led government in India was strategically bringing vast tracts of forest land all over the country under state control. The opportunities to exploit forest resources were both lucrative and abundant once indigenous and forest-dependent communities had been divested of their rights and access to such forested land. Local communities struggled to find fodder for their cattle, timber and fuelwood–a necessity to sustain their livelihoods. The advent of the First World War raised the demand for timber at which time the hill communities in Uttarakhand organised a non-cooperation movement, strongly and surely resisting British management of their forest land.

The British administration took heed, and in a bid to appease the masses, set up a Forest Grievance Committee for Kumaon in 1921. The committee focused on understanding the main grievances of the people of the Kumaon region, with an emphasis on what their difficulties were, how they could be made part of the conservation efforts and how their cooperation with the Forest Department could be secured again. Forest Panchayat Act was enacted under Section 28(2) of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 in 1931.

Setting up of Van Panchayats was a part of the solution to give back some autonomy to the hill folk living in and around these forests. They could graze cattle on these lands and lopping of oak and kokat trees were allowed again. Van Panchayats facilitated a participatory approach to the management of forest resources. Back in 1921, a van panchayat was allotted land outside the reserved or protected areas. To form a van panchayat, the Gram Sabha would apply to the divisional commissioner for the formation of a van panchayat in the Gram Sabha.

Pauri, Uttarakhand via Pixabay

Challenges

Over time the need of Van Panchayats in Uttarakhand has increased. The state’s involvement in the management of forests is intensifying to pave the path for infrastructure, connectivity and developing industries to buttress economic development. Small players like rural communities, farmers, foragers and traditional foresters are side-lined as the revenue they generate for the state is relatively small compared to the large-scale commercial development—such as mining, timber, hydroelectricity etc. These neglected groups are responsible for taking up advocacy for the protection and conservation of forests. Forests play a critical function in the lives of the rural residents of Uttarakhand. Water harvesting and conservation, fuelwood and biomass, livestock feed, construction timber and food are services derived from the forest ecosystem.

Van Panchayats are gradually losing their autonomy with the introduction of Village Forest Joint Management Committees that are set up by the Forest Department. A top-down approach of the state and the central government has resulted in the formation of Van Panchayats where none were required and has created conflict over boundaries, jurisdiction etc. between forests. The irregular division of forest areas for the sake of creating village forests has led to the inequitable distribution of forest resources among villages as well, exacerbating the conflict further.

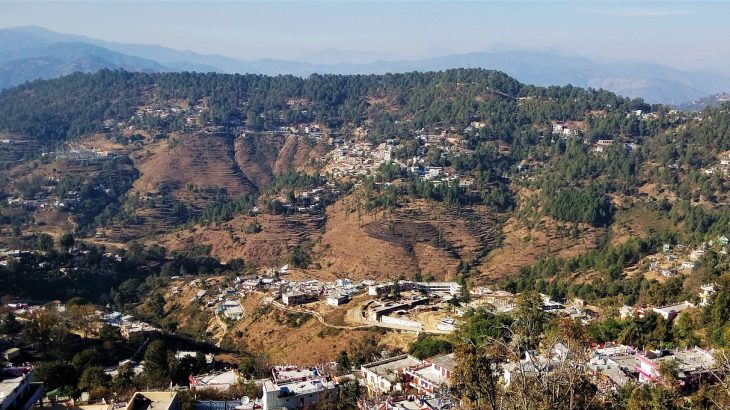

Almora, Uttarakhand via Pixabay

The way forward

To create community-centric institutions for the management of forests is the most efficient and cost-effective way of implementing conservation. Groups dependent on forests for food, livelihoods and shelter directly are more likely to be invested in the equitable and sustainable utilisation of forest resources. They benefit from the clean air, pure water, fodder for livestock, shrubs and herbs for medicine and vegetable and leaves for food. Any external agency that does not experience the forest, in the same way, will not be in a position to represent local interest with the same level of commitment. A careful study of the existing network of Van Panchayats, their leadership, the role of community participation and models of operation, will provide policymakers with a sound basis for implementing forest councils across the country with high ranging benefits to rural communities.